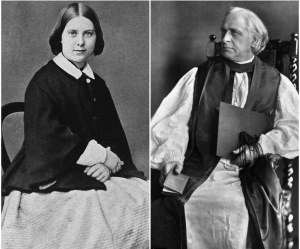

A FEW YEARS ago a biography over a Victorian Archbishop’s wife saw daylight. It got some attention in British press. Mary Benson (1841-1918) was an ordinary vicar’s wife whose husband one day became the Archbishop of Canterbury. Edward W. Benson (1829-1896) reached the highest office within the Church of England and of the world-wide Anglican communion. Author Rodney Bolt has used diaries, and novels written by the Benson’s to produce this biography. The time covers both Victorian and Edwardian England.

MUCH FUSS was reported in media about Mary Benson’s believed lesbian lifestyle after the death of her husband. She set up household with the previous Archbishop of Canterbury’s wife; Lucy Tait who was allowed to sleep in the same bed as Mary and on the late Edward Benson’s side. There’s not much which can confirm these circumstances today except from letters; diaries and our own conclusions.

MUCH FUSS was reported in media about Mary Benson’s believed lesbian lifestyle after the death of her husband. She set up household with the previous Archbishop of Canterbury’s wife; Lucy Tait who was allowed to sleep in the same bed as Mary and on the late Edward Benson’s side. There’s not much which can confirm these circumstances today except from letters; diaries and our own conclusions.

Mary Benson proved to be a very independent woman. The Victorian values of her time didn’t stop her to do what she wanted to. She was described by William Gladstone the British Prime Minister, as the ‘cleverest woman in Europe’. Despite all the Victorian values concerning women and the role of a woman in Mary Benson’s position she managed to keep up with a double-lifestyle as the wife of the Archbishop and a more private self. One of her children remember she was often away, seldom played with them or talked to them. As her diaries proves; this wasn’t an easy way of life. She had a lot of relations with women. She tried to reconcile these relations and feelings with faith and more devoution to her husband. Often pointing them out in the diaries she prayed a lot to be free from her “carnal affections”. At the death of her husband when she was 55 she could finally allow herself more freedom and set up household with long-time friend Lucy Tait.

A Victorian Marriage

IT WAS CREEPY to learn that Edward W. Benson befriended Mary as an eleven-year-old child and thought of her as a future bride to marry. Perhaps this wasn’t an unusual situation among the Victorians that men from the middle classes could search for future brides in a similar way. Mary Sidgwick was also his 2nd cousin and the families knew each other well. He writes about the “friendship” in his diary:

“As I have always been very fond of [Minnie] and she of me with the love of a little sister, and as I have heard of her fondness for me commented on by many persons, and have been told that I was the only person at whose departure she ever cried, as a child, and how diligent she has always been in reading books that I have mentioned to her, and in learning pieces of poetry which I have admired, it is not strange that I, who from the circumstances of my family am not likely to marry for many years to come, and who find in myself a growing distaste for forming friendships (fit to be so called) among new acquaintances and who am fond indeed (if not too fond) of little endearments, and who also know my weakness for falling suddenly in love, in the common sense of the word, and have already gone too far more than once in these things and have therefore reason to fear that I might on some sudden occasion be led [the following in cipher: into a step I might all my life repent] — it is not strange that I should have thought first of the possibility that some day dear little Minnie might become my wife.” (Bolt 2011, p.24)

WE DO HAVE the adult Mary Benson’s thoughts on these circumstances:

“I realise that he chose me deliberately, as a child who was very fond of him and whom he might educate — he even wanted to preserve himself from errant fallings-in-love... God, though gavest me a nature which desired to please — and on its natural gaiety and natural-lovingness had been planted by my Mother a strong sense of duty. . . .” (Bolt 2011, p. 25)

SADLY as noted from her diary entrance we can relate exactly to how she was brought up in her social environment – to “please” and be aware of ones “duty”. As commented on by the author she was also below the age of consent when Edward W. Benson wrote his diary entrance. The consent age for girls in the 1850s was twelve. 25 years later the age was raised to thirteen. In 1885 it was raised to sixteen years thanks to the Criminal Law Amendment Act (Bolt 2011, p. 319). BUT AS this biography will reveal things went pretty well for the young lady. She managed to develop into an independent individual which was quite unusual considering her position as a vicar’s wife.

I THOUGHT the biography was quite interesting; and that its author did manage to carry out a well-researched project. WE shall be lucky considering the fact that the Victorians were excellent diary keepers and letter-writers. Communication through letters was the past times social media. Mail was delivered several times a day and on Saturdays too. It was the glory days of all postal offices. With such much material at hand I was a little disappointed the author fictionalized some parts. This is noted in the introduction and it’s no longer unusual writers of biographies today use this method.

The Children of the Bensons

Despite modern assumptions on lesbian sex at Lambeth Palace Mary Benson quickly gave birth to six children. Many of them would become great names themselves and seemed just as eccentric as their mother. Neither was the marrying type. Her daughter Maggie, Margaret Benson (1865-1916) became an Egyptologist who were among the first women in England to study at Oxford. She also took part in Archeological excavations i Egypt. Their son Arthur Benson wrote the lines for Land of Hope and Glory while Fred Benson wrote Adventure books. Robert Hugh Benson (1871-1914) shocked everyone and left his priesthood within the Anglican Church only to convert to Roman Catholicism. He was also a writer.

AFTER HIS CONVERSION to Catholicism Robert Hugh Benson received a lot of hate-mail! Men, women and even little school girls wrote nasty letters to the most unspeakable human being in the protestant kingdom! The defection didn’t go unnoticed in the press either. Finally, he moved. He had a long career in the Roman Catholic Church and in Rome he became a chamberlain to the Pope, 1911 and was entitled monsignor. Robert Hugh Benson was also a writer of fiction and wrote a very popular novel The Lord of the World (1907).

It’s considered one of the first modern dystopian novels. It has been called ‘prophetic’ by Pope Benedict XVI and Pope Francis. And the Story’s Main Themes? The Lord of the World is about the Anti-Christ and his reign on earth. And the story goes as follows – Since the Labour Party took control of the British Government in 1917, the British Empire has been a single party state. The British royal Family been deposed, the House of Lords has been abolished, Oxford and Cambridge have been closed down, and all their professors sent into exile in Ireland. Marxism, Atheism and Secular Humanism which one of the novel’s protagonists describes as the tools of Freemasonry dominate culture and politics. The world now has only three main religious forces: Catholicism, Secular Humanism, and “the Eastern religions”. Blaming “subgroups” in society are what we today may define as conspiratory behaviour. His horror and ghost fiction are collected in The Light Invisible (1903) and A Mirror of Shallott (1907). Many of the Benson’s children had mental problems all their lives. We don’t know about any diagnosis, but bipolar disorder may be a rational explanation today. Maggie Benson was deeply affected and died only 50 after a mental breakdown.

The Benson Brothers reflect upon their parents marriage

Arthur Benson (1862-1925):

Arthur: [….] It was a case of real natural incompatibility. Mama was an instinctive pagan, hence her charm. Papa was an instinctive puritan with a rebellious love of art. Papa on the whole hated and distrusted the people he didn’t wholly approve of. Mama saw their faults and loved them. How very few friends Papa ever had. […] He disliked feeling people’s superiority. His mind was better and stronger than his heart and his heart didn’t keep his mind in check. It was a fine character, not a beautiful one. He certainly had a tendency to bully people as he believed from good motives. Mama never wanted to direct or interfere with people and I think was the most generous and disinterested character I have ever known. But her diary is very painful to me because it shows how little in common they had and how cruel he was. [Bolt 2011, p. 217]

Fred Benson (1867-1940):

Fred: Papa was a very difficult person to deal with, because he was terrifying, and remembered things, not very accurately, because he remembered the points which were in his favour and forgot the points which were not. Mama forgot everything, or is she remembered, forgot the sense of resentment. Then he wanted, as you say, obedience and enthusiasm. Mama never claimed either exactly, but got both. Then Papa cared intensely about details, and details never interested Mama; and one must remember, as you say, the other side — and Papa’s affection, when it rose to the surface, was very revealing indeed. [From correspondence between the two brothers in 1925. [Bolt 2011, p.p 217-218]

Sources

Bolt, Rodney. As Good as God, as Clever as the Devil: The Impossible Life of Mary Benson. London: Atlantic Books, 2011.

Wikipedia.org